The Malaspina Expedition – the Spanish reaction to Lapérouse’s voyage

by Pierre Bérard

The Spaniards were the first to conquer the American Pacific Ocean from 1520 onwards, first of all departing from Panama towards the coast of South America, and discovering at the same time the Strait of Magellan, during the first voyage around the globe. They later developed their territorial occupation all along the coasts of North and South America, as Lapérouse was able to note in 1786 in his two calls at Concepción (Chile) and Monterey (Upper California). In addition, Magellan’s successors in the Philippines occupied this archipelago, especially in its northern part (Luzon), declaring it, along with the Mariana Islands, a Spanish colony attached to Mexico. But the Pacific Ocean itself, outside the routes from Acapulco to Manila (outbound with the trade winds and inbound with the westerlies in the higher latitudes) was not the object of a very sustained programme of Spanish exploration.

The Spaniards were the first to conquer the American Pacific Ocean from 1520 onwards, first of all departing from Panama towards the coast of South America, and discovering at the same time the Strait of Magellan, during the first voyage around the globe. They later developed their territorial occupation all along the coasts of North and South America, as Lapérouse was able to note in 1786 in his two calls at Concepción (Chile) and Monterey (Upper California). In addition, Magellan’s successors in the Philippines occupied this archipelago, especially in its northern part (Luzon), declaring it, along with the Mariana Islands, a Spanish colony attached to Mexico. But the Pacific Ocean itself, outside the routes from Acapulco to Manila (outbound with the trade winds and inbound with the westerlies in the higher latitudes) was not the object of a very sustained programme of Spanish exploration.

The voyages of James Cook from 1768 to 1778 were a big step forward in exploration, notably in the knowledge of New Zealand and eastern Australia, and also the northern and southern Polar regions. The voyage of Lapérouse, an important expedition by a nation allied to the Spaniards, was very revealing about the Spanish routine which had been established for 250 years along the American coasts. Lapérouse, who had stopped at Monterey on his way from Alaska, was engaged especially in an examination of the fur trade with China. He was a stimulus in this subject which also interested the Spaniards. Among them he got on well with Esteban Martinez, of the Spanish Royal Navy, to whom he pointed out the goals of the English, after those of Cook towards Behring Strait. Added to these was the advance of Russian outposts on the same coast, after their taking possession of the Aleutian and Kodiak Islands.

The Viceroy of Mexico, who had become anxious, then asked the Spanish Navy to verify the occupation of the northern coast with the aim of keeping an eye on Nootka on the western side of Vancouver Island, an outpost that was already known about, and also to record the advance of the Russian outposts on the Northern Pacific coast. The results caused much surprise. In 1789, Vancouver Island was transformed into a trading post for English ships and a few American ones, after America had recently become independent. After the expulsion of the Anglo-Americans and the construction of the Spanish fort of San Miguel at Nootka by this same Martinez who had met Lapérouse, diplomatic discussions had accepted the rather vague principle that “to possess a territory, first of all it has to be occupied.” This idea, skillfully interpreted by the English, ended later in the creation of British Columbia, an extension of their Canada. As for the Russians, they quickly occupied the coasts of Alaska, with their capital at Sitka, without worrying too much about rights of occupation.

A few months earlier at Concepción, Lapérouse had met Ambrosio O’Higgins, an Irish Catholic who had become a Spanish official, who had welcomed the French expedition. That did not prevent him, when reporting to Madrid, from requesting the organization of an equivalent Spanish expedition. The Italian Alessandro Malaspina, an officer in the Spanish Navy, who had previously fought a great deal against Algerian and Moroccan pirates in 1776 and who knew the Philippines well, had also met O’Higgins in Concepción after crossing the Pacific. This is why the Governor had applied to his government for a Spanish scientific expedition in the Pacific, capable of being compared to that of Lapérouse, which was to be entrusted to Malaspina. The latter was then ordered to oversee, in the La Carraca shipyards in Cadiz, the construction of two corvettes, 35 metres long with a draft of 4.34 metres, rather similar to Lapérouse’s ships, named Discubierta (Discovery) commanded by Malaspina, and Atrevida (Audacious) commanded by Joseph de Bustamente. The crew included a high-level scientific nucleus, both for cartography as well as the study of animals, plants and minerals, along with the artists who were indispensable for the sketching of the countryside and various other subjects. The ships set sail from Cadiz in July 1789, initially for an extensive voyage along the Pacific coasts, calling into Spanish ports then, in summer, sailing up the coast as far as the Gulf of Alaska, measuring the height of Mount Saint Elias [5,489 metres, the second highest mountain in both the USA and Canada, situated on the Yukon/Alaska border] and stopping off in Yakutat Bay, identified by Lapérouse. A large glacier in this region was named after Malaspina. The aim was to complete the cartography outside the usual Spanish areas (Prince William Island) and to observe the state of the foreign settlements, linked mainly to gathering furs in the cold areas. The expedition then identified Puget Sound, the very large entry passage to Vancouver Bay that Lapérouse, passing by too far out to sea, had not suspected.

He finally left the American coast at Acapulco and made a classic outbound passage with the tradewinds towards Guam and the Philippines (repair of the ships and rest for the crew) and Macao (evaluation of the potential of the trade in furs and other Asian goods in America). He then set out for the exploration of the northern part of New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, sailing as far south as the southern part of New Zealand to complete Cook’s mapping (Doubtful Sound), then the mapping of uncharted parts of Australia, putting in to allow a courtesy call and observation of Port Jackson (Sydney), a colony that was already five years’ old. He feared that the British outpost would become a maritime threat to the Philippines (but at that period there were very few British ships stationed there), thinking also about a commercial treaty between Australian and Chile, whose livestock and agricultural resources had, at that time, a huge surplus.

In spite of the length of his voyage which, in the end, lasted four years and three months, he again left Sydney to cross the Pacific, stopping for a month at Vava’u in the Tonga group, then exploring a few islands on his way to Callao. On the return voyage to Spain, via Tierra del Fuego, he mapped the Chilean fjords and the Falkland Islands. He finally returned to Cadiz with his crew in quite good health, free of scurvy, and with a wealth of mineral and plant specimens at least the equivalent of Cook’s.

—————————————————-

This article appears in volume No63/Spring 2015 issue of the ‘Journal de bord’, journal of the Members of the Association Lapérouse Albi-France. It was translated by Dr. William Land, with the permission of the author, Monsieur Pierre-Louis Bérard.

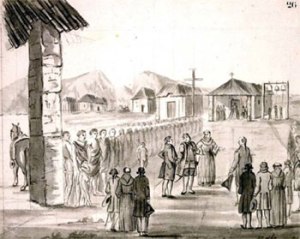

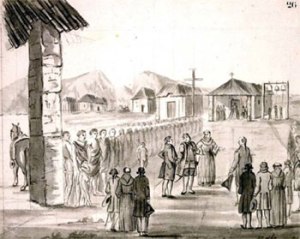

More about Lapérouse in Monterey ( image: Lapérouse at Carmel by Gaspard Duché de Vancy in 1786)

You must be logged in to post a comment.