CLAUDE-FRANCOIS-JOSEPH RECEVEUR

“Long, long ago, his grave was made

Beside the headlands grim;

Though blossom fade, he shall not fade;

There is no death for him.”

From the poem “Pere Louis Receveur” by Roderic Quinn, The Crusader, 1st June, 1933.

Born on 25thApril, 1757 at Noel-Cerneux(Doubs), Receveur was given the name of Father Louis when he entered the order of Friars Minor (founded by Saint Francis of Assisi in 1109).He served in the French Navy, from 1776 to 1780, presumably as a chaplain, but it was also for his knowledge as a geologist, specialising in the study of volcanoes, that he was chosen by Laperouse and the King as naturalist on board the Astrolabe. Laperouse found him to be a “naturaliste infatigable”, and wrote:

“The priest Receveur discharges the sacred duties of his office with the greatest dignity and is a man of amicable manner and good sense. At sea he is occupied in meteorological and astronomical observations and when he is in port attends to everything relating to natural history.”

He arrived in Botany Bay with the Laperouse expedition on 26th January, 1788 and died there three weeks later on 17th February, 1788.

Although the circumstances of Pére Receveur’s death remain somewhat obscure, it has been assumed that he succumbed to wounds received in the confrontation with natives at Tutuila, Samoa, on 11th December, 1787, when Captain de Langle and eleven members of the Laperouse expedition were brutally massacred.

Receveur was buried on the La Perouse headland and his grave marked by a headstone and a board bearing the inscription: Hic jacet Le Receveur E.F.F. Minimis Galliae Sacerdos, Physicus in circumnavigatione Mundi Duce De La Peyrouse Ob. 17 Feb. 1788 was nailed to a tree.

On the 4th April, 1788 Lieutenant William Bradley visited the site and recorded in his journal that the grave marker was found to have been torn down by the natives and that the inscription was copied by one of the gentlemen and the same ordered by Governor Phillip to be engraved on a piece of copper and nailed in the place the other had been taken from. On 1st June, 1788 John White, Surgeon-General on the First Fleet, visited the site and noted in his diary that the grave was truly humble indeed, being distinguished only by a common head-stone, struck slightly into the loose earth which covered it. He also noted that we cut down some trees which stood between that on which the inscription is fixed and the shore, as they prevented persons passing in boats from seeing it….and that at some future day he(Governor Phillip) intends to have a handsome head-stone placed at the grave.

When Louis Isidore Duperrey’s expedition arrived in New South Wales on the Coquille in 1824, some of the officers went in search of the Lapérouse campsite and Receveur’s grave. One of them, Ensign Victor-Charles Lottin recorded meeting the garrison of a corporal and two soldiers and asking them whether they knew of a French tomb in the neighbourhood of their fort. The corporal took Lottin and his companions to a place where the earth was raised and covered with grass. They found no marker so on the trunk of an enormous Eucalyptus which shaded the site, they carved the words: Prés cet arbre reposent les Restes du P. le Receveur visite en Mars 1824. The tree was later used as a windbreak for a fire, but the stump with the carved inscription was saved due to the efforts of Simeon Pearce. (Photo: detail of inscription.)

When Louis Isidore Duperrey’s expedition arrived in New South Wales on the Coquille in 1824, some of the officers went in search of the Lapérouse campsite and Receveur’s grave. One of them, Ensign Victor-Charles Lottin recorded meeting the garrison of a corporal and two soldiers and asking them whether they knew of a French tomb in the neighbourhood of their fort. The corporal took Lottin and his companions to a place where the earth was raised and covered with grass. They found no marker so on the trunk of an enormous Eucalyptus which shaded the site, they carved the words: Prés cet arbre reposent les Restes du P. le Receveur visite en Mars 1824. The tree was later used as a windbreak for a fire, but the stump with the carved inscription was saved due to the efforts of Simeon Pearce. (Photo: detail of inscription.)

The Eucalyptus Stump

In 1854 it was decided to hold an Exhibition of Arts and Industry in Sydney as a preliminary to the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1855. Modelled on the Great Exhibition of Industry of All Nations held in London in 1851, the Paris exhibition had been initiated by Louis Napoleon and the colonial version too would imitate this extraordinary collection of objects. For the preliminary exhibition in Sydney, the organisers had selected the Hall of the Australian Museum. Shortly before the opening of the exhibition, the organisers ordered that the tree stump with Receveur’s epitaph be cut down, displayed at the exhibition and then sent to France. There it would be exhibited at the Paris Universal Exhibition. (Photo: sketch 1842 by Oswald Brierly)

The inscribed tree stump was seen by the organisers, the public and the press at the time as a symbol of the colonial ties with France. The Illustrated Sydney News proclaimed that the French would be pleased that such an object was preserved with almost sacred respect through so many years out of respect for the intelligence and enterprise of a member of their own nation.

Before its removal, a water colour depicting the stump in situ beside the tomb of Receveur, with the Lapérouse Monument in the distance, was commissioned from the Sydney artist Frederick Terry. The watercolour was displayed above the stump at the Sydney exhibition. After the Paris exhibition the stump was donated to the La Perouse Museum, then in the Louvre, Paris. The water colour was later taken by Sir William Macarthur where it too was presented to the Louvre, Paris.

Before its removal, a water colour depicting the stump in situ beside the tomb of Receveur, with the Lapérouse Monument in the distance, was commissioned from the Sydney artist Frederick Terry. The watercolour was displayed above the stump at the Sydney exhibition. After the Paris exhibition the stump was donated to the La Perouse Museum, then in the Louvre, Paris. The water colour was later taken by Sir William Macarthur where it too was presented to the Louvre, Paris.

From 1855 the stump has remained in the collection of the Louvre and the Musée de la Marine Paris. In 1988 the stump along with a collection of objects from the Lapérouse expedition were presented to the Lapérouse Museum as part of France’s gift to the Australian people for Australia’s bicentennial. In 2008, the stump was returned to the Musée de la Marine Paris for an exhibition on Lapérouse and remains there.

The Brass Replica

In 2012, at the request of the Friends of the Lapérouse Museum, Randwick City Council commissioned a bronze replica of the original tree stump. The work was undertaken by the Fonderie Lauragaise under the direction of Monsieur and Madame Ramon.

On 13 November , 2012, the spectacular operation of casting the eucalyptus tree trunk took place…the preparation of the double-walled mould made of graphite, resistant to molten metal at 1200o, is rather complex. A first impression is taken in élastomère and is then transferred to the mould with a vessel inside which contains a complex pipe system, to ensure a good dispersal of the bronze and the progressive elimination of air and burning gases. The mould itself is heated to 800o in an autoclave to avoid any thermal shock. This operation, which includes rapid and dangerous handling manoeuvres is critical. In case of serious imperfections, there is nothing to do but to make another mould and a new casting.

After cooling, removal of the pipe system and the interior and exterior moulds, and repair of slight imperfections, the process remains a long job, in several stages, a little like that of leather [tanning] which changes a rough unattractive material into a product that is pleasant to look at and to touch, true to the original.

In April 2013, the bronze trunk was sent by diplomatic post to Australia, courtesy of the French Ambassador, Stéphane Romatet. It arrived at the Laperouse Museum on the 24th.

The Story of the Eucalyptus- a tree of many names

The Story of the Eucalyptus- a tree of many names

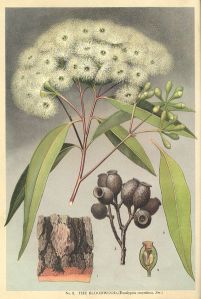

The tree was probably a Corymbia gummifera, named gummifera for the red resin it exudes. Material from a specimen was first collected in Botany Bay by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander on the 1770 Cook Expedition, and described in 1788 by German botanist Joseph Gaertner as Metrosideros gummifera. On Cook’s third expedition in 1777, botanist David Nelson collected a eucalypt on Bruny Island. This was later described by French botanist Charles Louis L’Héritier who named the genus Eucalyptus, referencing the operculum of the flower bud – from the Greek eu and calyptos, meaning well covered.

James Smith described the Botany Bay tree as Eucalyptus corymbosa in his 1793, A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland. French botanist, René Louiche Desfontaines recorded it as Eucalyptus oppositifolia in 1804. Swiss botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle, in 1828 described it as Eucalyptus purpurascens var. petiolaris. The Director of the Botanic Gardens in Sydney, Joseph Maiden in his revision of the genus in 1920 called it Eucalyptus longifolia, this time the species name referenced the length of the leaf. Gaetner’s original species name of gummifera was recognised in 1925 by Swiss botanist Bénédict Pierre Georges Hochreutiner. It remained as Eucalyptus gummifera until 1995 when the Eucalyptus genus was split into three genera - Eucalyptus, Angophora and Corymbia - by Australian botanists Laurie Johnson and Ken Hill.

James Smith described the Botany Bay tree as Eucalyptus corymbosa in his 1793, A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland. French botanist, René Louiche Desfontaines recorded it as Eucalyptus oppositifolia in 1804. Swiss botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle, in 1828 described it as Eucalyptus purpurascens var. petiolaris. The Director of the Botanic Gardens in Sydney, Joseph Maiden in his revision of the genus in 1920 called it Eucalyptus longifolia, this time the species name referenced the length of the leaf. Gaetner’s original species name of gummifera was recognised in 1925 by Swiss botanist Bénédict Pierre Georges Hochreutiner. It remained as Eucalyptus gummifera until 1995 when the Eucalyptus genus was split into three genera - Eucalyptus, Angophora and Corymbia - by Australian botanists Laurie Johnson and Ken Hill.

(Botanical Illustration by Western Australian artist Edward William Minchen, appeared in Joseph Maiden’s The Flowering Plants and Ferns of NSW).

Pingback: Peré Le RECEVEUR, died 17 Mar 1788 La PerouseAustralian History Research

Pingback: Receveur Anniversary 2021 | La Perouse Museum & Headland