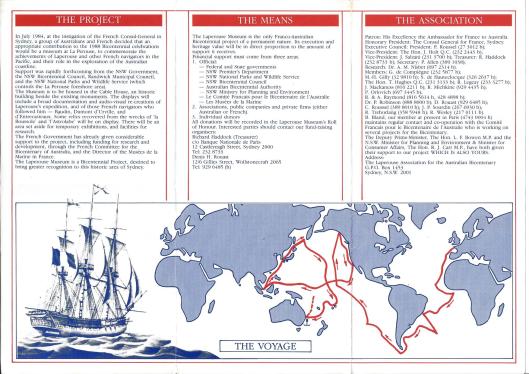

On 9 April 1787, La Boussole and L’Astrolabe set sail from Cavite (Philippines). A month and a half later, having risked their all near the coast of Formosa (today Taiwan), the two frigates reached a position off the coast of Quelpaert, the largest island of the Kingdom of Choson (the name under which Korea was known in the 18th century), about 80 km south of the peninsula. This island guarded the entry to the Strait of Korea[1] and, by this fact, access to the Eastern Sea (or Sea of Japan). This coast had already been mentioned with more or less precision on the maps and portolans[2] drawn up by the Chinese and circulated by the Jesuit missionaries, but no Western ship had yet ventured into these waters…

On 9 April 1787, La Boussole and L’Astrolabe set sail from Cavite (Philippines). A month and a half later, having risked their all near the coast of Formosa (today Taiwan), the two frigates reached a position off the coast of Quelpaert, the largest island of the Kingdom of Choson (the name under which Korea was known in the 18th century), about 80 km south of the peninsula. This island guarded the entry to the Strait of Korea[1] and, by this fact, access to the Eastern Sea (or Sea of Japan). This coast had already been mentioned with more or less precision on the maps and portolans[2] drawn up by the Chinese and circulated by the Jesuit missionaries, but no Western ship had yet ventured into these waters…

Lapérouse now began one of the most innovative parts of his voyage, as was pointed out to him in the Mémoire du Roi pour servir d’instruction particulière au sieur de La Pérouse[3] : “Taking care, he will visit the western coast of Korea and the Gulf of Haon-Hay (Yellow Sea) without penetrating too far into it, and always retaining the ability to easily round the southern coast of Korea by using the south-westerly and southerly winds. He will then explore the eastern coast of this peninsula, the Tartary coast, where there is a pearl-fishing industry, and the coast of Japan opposite. All these coasts are absolutely unknown to Europeans.” [Note formation of volcanic rock on this World Heritage Listed site similar to the ‘miniature Giants Causeway’ at La Perouse]

Quelpaert Island (today’s Jeju-do link to photos)

Quelpaert Island (today’s Jeju-do link to photos)

When in sight of Quelpaert Island, Lapérouse was careful. He knew that, for centuries, Korea was a closed country, where all contact with the inhabitants was forbidden. In the books[4] brought on board in Brest, he read the story of the unfortunate Dutchman, Hendrick Hamel, and his companions, shipwrecked in 1653 and kept captive for more than 13 years.

“This island is known to Europeans only from the shipwreck of the Dutch vessel ‘Sparrowhawk’ in 1635 [1653] and was at the time under the rule of the King of Korea; we sighted it on 21st May with the best possible weather and the most favourable conditions for observations of distances. We determined the latitude of the southern tip to be 33o14’ [north], with longitude 124o15’ [east]. I sailed along the south‑east part of the coast, two leagues offshore, and we noted with the greatest care a feature measuring 12 leagues which M. Bernizet mapped. It was hardly possible to see a finer sight, a peak[5] of about a thousand toises[6], which could be seen from a distance of 18 to 20 leagues, rising in the middle of the island where water doubtless collects; and the land slopes gently down to the sea, where the houses are arranged in a semicircular fashion on rising slopes. All the ground appeared to us to be cultivated for a long way up the slopes. We could see, with the aid of our telescopes, the divisions between the fields. They seemed to be divided into many plots which proves a large population. The different crops produced very varied colours which made the appearance of this island even pleasanter. It belongs unfortunately to a population to whom all communication with foreigners is forbidden and which however keeps in slavery those who have the misfortune to be shipwrecked on its shores. Some of the Dutchmen from the ship ‘Sparrowhawk’ found the means, after 18 [13] years’ captivity during which they received several beatings, of taking possession of a ship and getting to Japan, from which they went to Batavia and finally to Amsterdam. This story, which we had under our noses, was not conducive to us sending a boat to the shore from which we could see two canoes stand out. But they came no closer than a league away, and it is probable that they had no other object than to observe us and perhaps raise the alarm all along the coast of Korea.”

The Dutch named this island “Quelpaert” (today Cheju-do or Jeju-do) as they found that it had the shape of a galiote[7] (a type of Dutch trading vessel) and “Quelpaert” is the slang word for these ships. Bernizet drew the coast, limited to the west by the peninsula marked ‘A’ on the map, a circular volcanic crater (Mount Ilchilbong, 180 metres high) linked to the coast by a narrow strip of land.

Continental coast of Korea and Cape Clonard (today’s Cape Homi)

Continental coast of Korea and Cape Clonard (today’s Cape Homi)

Having rounded Quelpaert Island to the east, Lapérouse stood into the Strait of Korea and preferred to sail along the Korean shore, less well known than the Japanese coast. “The channel that separates the coast of the continent from that of Japan may be 15 leagues wide; but it narrows to ten leagues because of rocks which, from Quelpaert Island, continue to line the western shore of Korea and which finally ended only when we had rounded the south-east tip of this peninsula; so that we were able to follow the continent very closely, [and] see houses and towns[8] which are on the seaside, and to reconnoitre the entrance to the bays […] We counted a dozen champans [sampans] which sail along the coast. They did not seem to me to differ in any way from Chinese ones, their sails were similarly made from matting and the sight of our vessels seemed to cause them only very little dread; it is true that they were very close to shore and they would have had time to reach it before we should close with them, if our maneuvering had raised some suspicions. I would very much have liked them to have dared to come alongside us but they continued on their course without bothering with us. The sight that we provided to them, although very new, did not seem to excite their attention. I saw however at 11 o’clock two ships set sail to look us over, come as close as a league away, to follow us for two hours, and then return to the harbour from which they had set out in the morning. Thus it is probable that we had caused alarm along the coast of Korea, all the more so as in the afternoon, [signal] fires were seen on all the headlands.”

These coastal signals (smoke by day, fires at night) gave the alert and, if necessary, they were relayed from mountain to mountain as far as Seoul where there was a central station. The aim was to rapidly inform the capital of the arrival of a possible invader.

The “day of the 26th was one of the most beautiful of our journey and one of the most interesting from the plots that we had carried out of a coastal settlement of more than thirty leagues.“ Lapérouse named the eastern tip of Korea ‘Cap Clonard’, from the name of his second-in-command of La Boussole. The former Cape Janggi of the Japanese is, since 2001, Cape Homi, famous for its octagonal brick lighthouse, built in 1908 by a French architect. Taking advantage of this fame, the Koreans have set up a national museum there, devoted to lighthouses, and have developed a broad esplanade, the “Park of the Rising Sun” where, on the evening of 31st December, a big festival takes place to celebrate the first sunrise of the new year. Satisfied with his navigation, Lapérouse noted in his journal: “we had sailed past the most easterly part and had determined the most interesting stretch of the coast of Korea.” It was now time to turn east in the direction of Japan.

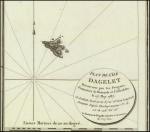

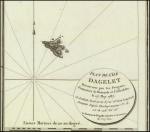

Dagelet Island (today Ulleung-do - read further)

Dagelet Island (today Ulleung-do - read further)

On 27th May, approximately 20 leagues from the Korean coast, the French sighted a small wooded island which did not appear on any map. They baptized it ‘Dagelet Island’, for “our astronomer saw it first.’

This island, today named ‘Ulleung-do’[9], is the furthest outlying possession of South Korea[10]. “It is scarcely more than three leagues in circumference: its north-east tip lies at 37o2’ north latitude, and 129o2’ east longitude. It has very steep slopes, [which are] covered from the summit to the water’s edge, with the most beautiful trees. A stretch of solid rock, almost as steep as a large wall, surrounds it completely, with the exception of seven small sandy coves in which it is possible to get ashore; it was in these coves that we saw, in a shipbuilding yard, boats of quite Chinese shape. The sight of our vessels, which passed with short cannon-shot, had doubtless frightened the workers, and they had fled into the woods which was no more than fifty paces from their yard. We saw, moreover, only a few huts without a village or any cultivation. Thus it is very likely that the Korean carpenters, who were only about twenty leagues from Dagelet Island, spend the summer on the island with provisions, to build boats there that they sell on the mainland. This opinion is almost a certainty as, after we had rounded the western tip, the workers in another shipyard who had not been able to see the ship, hidden by this headland, were surprised by us at work with their timber, building their boats; and we saw them flee into the forest, with the exception of two or three in whom we did not seem to inspire any fear. I wanted to find an anchorage to persuade these people by good deeds that we were not their enemy, but rather strong currents pushed us away from land. Night was starting to fall and I was forced to order my cutter, by signal, to return just as M. Boutin was going ashore, for fear that I would be borne to leeward and not be able to fetch him.” It was out of the question to take risks and Boutin returned on board. The exploration of Korean waters was finished. The expedition now made its way towards other unknown lands, in the Tartary Channel [Strait of Tartary].

This island, today named ‘Ulleung-do’[9], is the furthest outlying possession of South Korea[10]. “It is scarcely more than three leagues in circumference: its north-east tip lies at 37o2’ north latitude, and 129o2’ east longitude. It has very steep slopes, [which are] covered from the summit to the water’s edge, with the most beautiful trees. A stretch of solid rock, almost as steep as a large wall, surrounds it completely, with the exception of seven small sandy coves in which it is possible to get ashore; it was in these coves that we saw, in a shipbuilding yard, boats of quite Chinese shape. The sight of our vessels, which passed with short cannon-shot, had doubtless frightened the workers, and they had fled into the woods which was no more than fifty paces from their yard. We saw, moreover, only a few huts without a village or any cultivation. Thus it is very likely that the Korean carpenters, who were only about twenty leagues from Dagelet Island, spend the summer on the island with provisions, to build boats there that they sell on the mainland. This opinion is almost a certainty as, after we had rounded the western tip, the workers in another shipyard who had not been able to see the ship, hidden by this headland, were surprised by us at work with their timber, building their boats; and we saw them flee into the forest, with the exception of two or three in whom we did not seem to inspire any fear. I wanted to find an anchorage to persuade these people by good deeds that we were not their enemy, but rather strong currents pushed us away from land. Night was starting to fall and I was forced to order my cutter, by signal, to return just as M. Boutin was going ashore, for fear that I would be borne to leeward and not be able to fetch him.” It was out of the question to take risks and Boutin returned on board. The exploration of Korean waters was finished. The expedition now made its way towards other unknown lands, in the Tartary Channel [Strait of Tartary].

The shipwreck of the Sperwer (1653)

The Sparrowhawk cited by Lapérouse was the Dutch vessel Sperwer, en route for Nagasaki, which was driven ashore by a storm on 16th August 1653, on the south-west of the island of Jeju-do. Forty metres long by 7.5 metres wide, this ship belonged to the Dutch East India Company (VOC; Vereenigde Oost‑Indische Compagnie). The 36 survivors, out of a crew of 64 men, were captured, sent to Seoul and forced to serve at the King’s court. In 1667, eight men escaped and reached Japan from which they reached Batavia. Upon his return to Amsterdam, the supercargo[11] of the Sperwer, Hendrick Hamel, published his journal which, for more than a century, was the only description of the “Hermit Kingdom.”

Today, at Sanbangsan, a path goes down to the spectacular Yongmeori shore where a replica of the Sperwer has been built. Inside the ship, a permanent exhibition tells the story of 17th century Korea and Hamel’s adventure. The story of Hendrick Hamel, Relation du naufrage d’un vaisseau hollandais sur la côte de l’île de Quelpaert et description du royaume de Corée, was published in Dutch in 1668 and in French in 1670. It was republished by L’Harmattan in 1985.

Dagelet Island, by Dagelet

“You will see upon our return that, in spite of many annoyances, we have done many good things in the Seas of China and Japan. I can tell you that I own, without however wishing to live there, a small piece of land called Dagelet Island. Certainly, if I could exploit the fine timber that covers all parts of it, it would be an inexhaustible source of wealth; probably there are also gold mines there, that circumstances did not allow us to explore. Industry there is pushed to a rather high degree of perfection, it is there that Korean vessels are built and we saw several on the slips whose shape seemed to us to be very well designed and a long way from the beginning of such a wonderful art.”

Letter from Dagelet to Prévost, dated 21 June 1787, and sent from Kamchatka. Centenaire de la mort de Lapérouse, Paris, Société de Géographie, 1888.

———————————————-

This article, by Bernard Jimenez, appears by kind permission of the Editor, ‘Journal de bord’, journal of the members of the Association Lapérouse Albi-France. It appears in issue No65, Autumn 2015. Translated by Dr. William Land AM.

[1] The name ‘Straight of Korea’ appears for the first time on one of the maps (plate No 43) in the ‘Atlas du Voyage de Lapérouse’, Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1797. All the British geographers of the 19th and 20th centuries have kept it as ‘Korea Strait’

[2] Charts based on compass readings and estimated distances drawn up by navigators at sea.

[3] Bibliothèque Mazarine, Ms 1546.

[4] In the inventory of the library on board, we find Découvertes dans les voyages de la mer du Nord, which must be Recueil de voyages au Nord [‘Collection of Voyages to the North (Sea), by Jean-Frédéric Bernard (1720) and Histoire générale des voyages [‘General History of Voyages’] by Abbé Prévost (1746). Both books include Hamel’s story.

[5] It was Hallasan, [Mount Halla] (1950 m), a volcanic cone that towers above the island.

[6] An old French measure equivalent to 6 feet approximately.

[7] A flat-bottom, seagoing sailing barge, with good sheer used in the small coasting trade of Germany, the Scandinavian countries and northern waters of Holland. It was keel-built with an overhanging clipper stem, and a round stern with vertical sternpost and outboard rudder. (René de Kerchove, International Maritime Dictionary, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1983, pp.321-322.)

[8] On the « Carte des découvertes faites en 1787 dans les mers de Chine et de Tartarie […] 1ère feuille », plate No 43 in the Atlas, it is shown to the south of Cap Clonard as “ville et fort de Tso-Choui.” This is the Chinese name of the city of Ulsan, as it appears on the Jesuits’ map. The fort was built in the 16th century by the Japanese. A point of history (economic): it is at Ulsan that the tanker “Lapérouse” was built by Hyundai Heavy Industries. It belongs to the Géogaz Company and transports liquefied petroleum gas.

[9] The island was still named ‘Dagelet Island’ in the San Francisco Peace Treaty between the Allied Forces and Japan on 8 September 1951.

[10] It is reached by ferry from Pohang (3 hours).

[11] A person appointed by the owners of the cargo on a merchant ship whose business is to manage the sales or purchases of goods and to superintend all the commercial aspects of the voyage. (René de Kerchove, op.cit.,p.807)

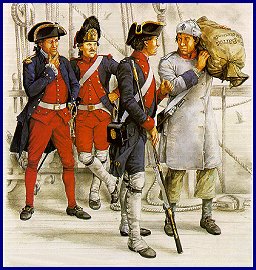

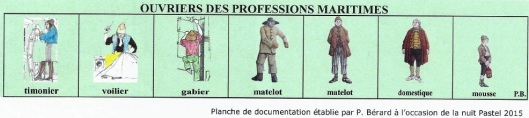

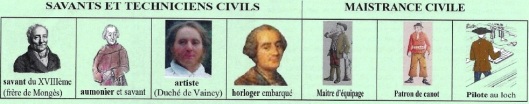

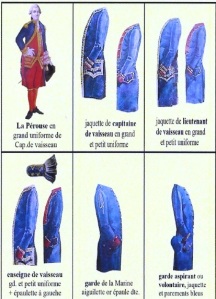

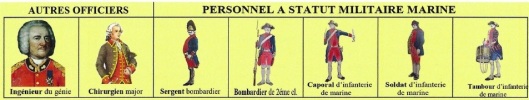

Officers (naval) (10): 1 captain (capitaine de vaisseau) (250 £) ; lieutenant (lieutenant de vaisseau) (135£) ; 3 or 4 sub-lieutenants (enseignes de vaisseau) (65£) ; 3 or 4 midshipmen (gardes de la marine)[3](30£)

Officers (naval) (10): 1 captain (capitaine de vaisseau) (250 £) ; lieutenant (lieutenant de vaisseau) (135£) ; 3 or 4 sub-lieutenants (enseignes de vaisseau) (65£) ; 3 or 4 midshipmen (gardes de la marine)[3](30£) Only the military [=naval] personnel wore uniform.

Only the military [=naval] personnel wore uniform.

You must be logged in to post a comment.