Tags

Crew list of an exploration flûte[1] with a note of the monthly wages in livres tournois[2]

Officers (naval) (10): 1 captain (capitaine de vaisseau) (250 £) ; lieutenant (lieutenant de vaisseau) (135£) ; 3 or 4 sub-lieutenants (enseignes de vaisseau) (65£) ; 3 or 4 midshipmen (gardes de la marine)[3](30£)

Officers (naval) (10): 1 captain (capitaine de vaisseau) (250 £) ; lieutenant (lieutenant de vaisseau) (135£) ; 3 or 4 sub-lieutenants (enseignes de vaisseau) (65£) ; 3 or 4 midshipmen (gardes de la marine)[3](30£)

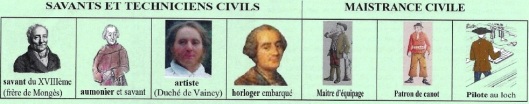

Scientists, artists, experts (7): scientists (200£); artists and experts (100£); chaplain (150£)

Senior naval ratings (3): chief petty officer (premier-maître) (60£); sergeant gunner (40£); assistant surgeon (50£).

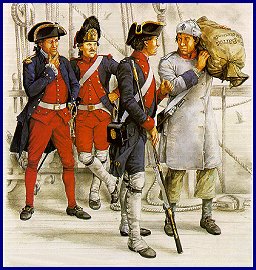

Landing party (8): in uniform when carrying out armed protection of shore parties: gunners, musketeers, drummers (40£).

Civilian senior ratings (27): with a contract to serve on board a King’s ship.

-navigation: boatswain (65£) and his assistants, pilots (being able to read and write and having received navigation training) (70£); assistant pilots (45£), boat captains (45£): in total, about a dozen people.

-maintenance: carpenter (55£); cooper (40£); caulkers (40£); sailmakers (55£); armourer and blacksmith (50£): in total, about ten men.

-victualling: purser (commis) (50£); cook (40£); butcher and baker (35£): four men.

Civilian crewmen (56): under contract on different rates of pay (20 to 30£)

Sailors: helmsmen, topmen, and [ordinary] sailors (about 38 men).

Gun crews, normally serving as sailors, except in action.

Generally about 111 men, of whom 21 were military [= naval].

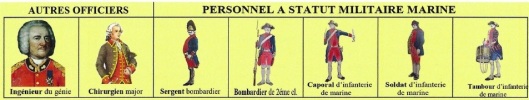

Illustrations by Pierre BÉRARD

Dress:

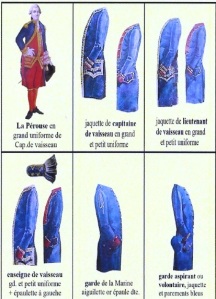

Only the military [=naval] personnel wore uniform.

Only the military [=naval] personnel wore uniform.

Naval officers of all ranks were dressed in red, over a white shirt (with a buttoned jacket, breeches covering the knee, and stockings). But the indication of their status and rank was worn on an outer blue coat (hence their name ‘officer of the blue’) which extended to the knee, and the end of whose sleeves were red and upon which their rank stripes were sewn, with a tricorn hat and white cockade. There were two versions for commissioned officers (captains, lieutenants and sub-lieutenants): a ceremonial uniform and a working dress, for routine duties on board ship, which had a red border on the upper part of the blue tunic. The rank was displayed on the sleeves and by gold lace on the edge of the tunic, on the edge of the side pockets and by epaulettes depending on the rank.

Sub-lieutenants had only one epaulette, bearing a lozenge-shaped device, worn on the left shoulder. The Volunteers, officers of a certain social standing but without official naval training, wore a completely blue uniform without facings or stripes. The midshipman (garde) wore a blue long coat, the end of whose sleeves were red, with a single aiguillette worn on the right shoulder.

The engineer[4] (specialist in fortifications of the Vauban[5]-type) was trained at Mézières (Ardennes) in a high-level school (the future École Polytechnique[6]) and wore a predominantly red uniform.

The surgeon[7] (grey jacket) was an officer on board, but not the assistant surgeons who did not enjoy the status of officer. The naval hospitals were run by physicians who were better educated than them.

Senior sailors and naval fighting personnel (gunners, marines) wore uniform during military operations and parades, especially carrying out armed protection of boats going ashore.

Civilian officers were dressed as gentlemen, the chaplains in a soutane and the technicians more simply.

Civilian senior sailors wore functional non-regulation clothes, but customarily according to their specialty and depending on the weather (shirt, waistcoat, trousers, socks, shoes or boots) generally with a hat or a cap, with a need for relative comfort.

The civilian workers wore, in the main, shirt, jacket, trousers (often made of striped cloth), a hat or cap, most often bare-foot on deck. They had very little spare clothing, which was kept in a bag or sea-chest, often to the point of risking minimal hygiene standards. The principal officers and scientists had their own servants on board, who were at the bottom of the pay scale.

[1] Store ship. Also a frigate, with reduced armament and crew, fitted out to carry cargo. (Pâris et Bonnefoux, Dictionnaire de Marine à voiles, Paris, Éditions du Layeur, 1999, p.328.

[2] Livre tournois (Tours pound) (£) was a unit of French currency which eventually became the French franc.

[3] These have no real equivalent in the British Royal Navy, the closest being ‘midshipman’. They were young men, destined to become naval officers. Before becoming a garde de la marine, one had to be previously an aspirant garde (an applicant), which required fulfilling a number of requirements, including being of noble birth, with documentary proof of this on the paternal side. These documents were examined by the genealogist of the royal Orders who drew up the appropriate certificate. The selection of the gardes was made by the King; the minimum age was 14 years and the maximum 18 years, and they had to be without physical deformity. Their family had to provide them with an annual allowance of 600 livres. They received instruction in mathematics, hydrography, English, Spanish, drawing, shipbuilding, fencing and dancing. They also received instruction in ship-handling and gunnery. (Jean Boudriot, Le vaisseau de 74 canons, Grenoble, Collection archéologie navale française, 1977, vol.4, pp.8-9)

[4] In the text, the title given is ‘ingénieur du génie interarmes’ which can be translated as ‘officer of the joint engineering corps’.

[5] Sébastien Vauban (1633-1707) was a Marshal of France who built a great many fortifications, as well as ports, canals and other civil engineering projects throughout France.

[6] Probably the most prestigious seat of higher learning in France; most of its graduates are engineers.

[7] In the text, the title is given as ‘chirurgien entretenu’ which can be translated as ‘supported surgeon’ or ‘navy‑appointed surgeon.’ This is a specifically French arrangement. In port, there was a certain number of experts, recognised for their skills, who received a special salary, and possibly other benefits. They were restricted to treating naval personnel, except by paying a fee. Apart from surgeons, there were other types of specialists ‘entretenus’ including engineers, teachers, and chaplains.

This article appeared in the ‘Journal de bord’, magazine of the Association Lapérouse Albi-France, No 66, Winter 2015; no author is noted). This article appears thanks to the courtesy of the Editor of the ‘Journal de bord.’ Translated by Dr W A Land AM.

The author also acknowledges the assistance with the translation of some of the technical terms by his cousin, Amiral (2S) Benoît Chomel de Jarnieu

Pingback: Life on board the ships of the Lapérouse Expedition | Lapérouse Museum & Monuments